Shingles, also known as herpes zoster, is a painful and often debilitating viral infection that affects millions of adults worldwide. It is caused by a reactivation of the varicella-zoster virus (VZV), the same virus that initially causes chickenpox. After recovering from chickenpox, the VSV becomes dormant, typically in the nerve cells of the body. They often stay dormant for years or even decades; however, under certain circumstances such as a weakened immune system due to stress, illness or aging, the virus can reactivate. The exact triggers for reactivation are not fully understood, but it is thought to be related to a decline in the immune system’s ability to keep the virus suppressed.

Shingles typically appear as a painful rash with blisters. This rash usually occurs on one side of the body and is most commonly seen on the torso or around the waist, but it can also affect the face and eyes. This is called herpes zoster ophthalmicus (HZO).

HZO presents with unique symptoms including:

In more severe cases, ocular manifestations can be extensive and potentially include every ocular structure. Nexus Eye Specialists, A/Prof Chameen Samarawickrama, Dr Anagha Vaze, Dr Rohan Gupta and Dr Phillip Myers discuss the serious ocular complications that can occur from shingles.

Shingles can cause a painful skin rash and blisters on one side of the face, including the forehead and eyelids. These blisters can also affect the cornea and cause inflammation and corneal ulceration.

While most cases of HZO can be treated effectively with anti-viral and topical medications, severe cases can lead to long-term corneal damage, scarring, corneal opacity and permanent vision loss. Some cases potentially require surgical treatment from eye specialists, such as corneal transplantation, or lifelong medications.

While retinal problems due to shingles are relatively rare, they can be serious and may result in debilitating vision loss if not addressed promptly.

VZV can cause inflammation of the internal structures of the eye and the blood vessels in the retina. It is a potentially blinding condition and needs prompt assessment and high-dose antiviral treatment, sometimes given intravenously. It also needs long-term topical and oral steroids along with low-dose oral antiviral treatment to prevent recurrences. Patients often require multidisciplinary care from eye specialists with close monitoring to avoid potential further complications such as increased intraocular pressure associated with long-term corticosteroids.

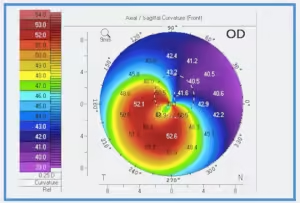

If VZV enters the anterior chamber of the eye, it can affect the drainage system, known as the trabecular meshwork, causing Trabeculitis. Inflammation can increase eye pressure and subsequently cause permanent damage to the optic nerve.

Another complication is the possibility of a steroid-induced increase in intraocular pressure (IOP). Vigilant IOP monitoring by eye specialists is required whilst patients continue their steroid treatment crucial for active intraocular inflammation. In most cases increased IOP can be managed with topical treatment, although in severe cases filtration surgery by an eye specialist may be required to protect the optic nerve and avoid vision loss.

When shingles affect the eye it can cause pain, often described as severe burning, itching, tingling or shooting pain. Sometimes this pain can continue even after the rash has healed, this is referred to as postherpetic neuralgia (PHN). It can be excruciating and long-lasting, persisting for months or even years. PHN is a result of nerve damage caused by the varicella-zoster virus during the initial shingles outbreak. The damaged nerves send pain signals to the brain even when there is no apparent cause for the pain. The risk of developing PHN increases with age. Management can be difficult, often requiring long-term pain relief, topical creams, and sometimes even psychological management and antidepressants need to be considered.

Whilst shingles can occur in an otherwise healthy adult, the risk increases with age and for those with weakened immune systems. Prevention measures suggested by eye specialists and general practitioners, like the Shingrix vaccine, have been shown to significantly reduce the risk of developing shingles, or lessen the severity of symptoms and the chance of developing more serious complications. From November 1st 2023 the Shingrix vaccine will be available to Australians aged 65 and older, First Nations people aged over 50 and immunocompromised people over the age of 18.

Copyright © 2023 Nexus Eye Care | Trans4m Business Consulting – Website Design & SEO | Privacy Policy | ^